This article is intended for professional advisers only and is not directed at private individuals.

In March 2017 I found a discrepancy between HMRC’s guidance for the Residence Nil-Rate Amount (RNRA) downsizing provisions and the legislation introduced to the Inheritance Act 1984 (IHTA) via Finance Act 2016 Schedule 15. Following a protracted review, HMRC recently informed me that the legislation has not been enacted in accordance with the government’s intentions. The consequence of which is that the statute in certain circumstances is accidentally more favourable to the taxpayer than intended, although this might better be understood as more in accordance with what the taxpayer expected in the first place.

The problems arise where a downsizing event has taken place and all or part of any remaining Qualifying Residential Interest (QRI) and other property passes to a surviving spouse or civil partner on first death rather than being “closely inherited” by descendants. If the property is closely inherited on the death of the second spouse/civil partner it might be expected that the “brought-forward allowance” provisions in IHTA s8G would act to maximise the available RNRA. However, it seems that it was the intent of the government to restrict the benefit of the transferability of the RNRA where a downsizing event has taken place.

Calculating the Downsizing Addition

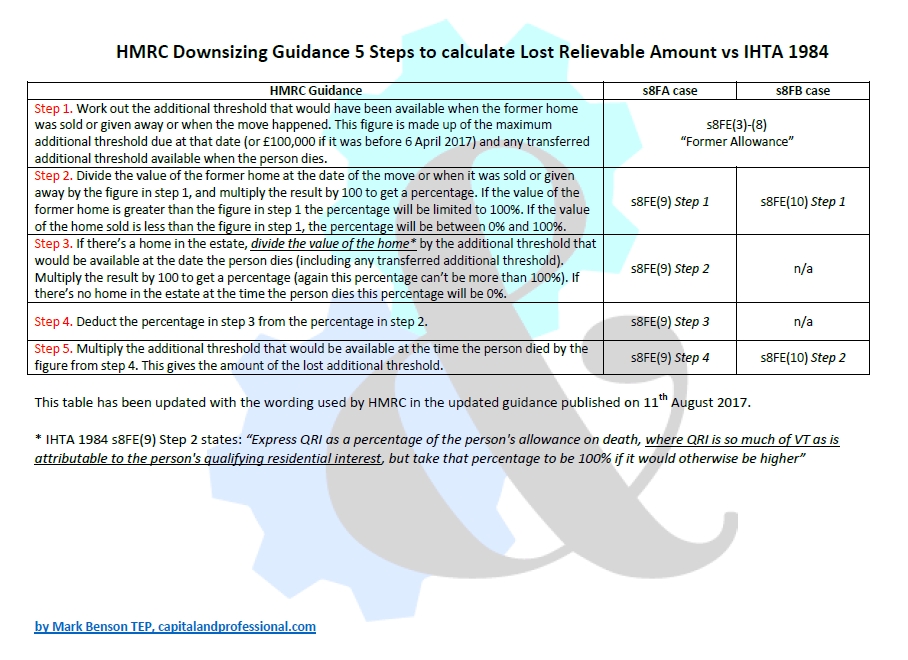

HMRC’s guidance acknowledges that the downsizing provisions are complex. In fact, they are so complex that they had to be introduced a year later than the basic provisions in 2016, and added a further 12 pages of statute to the 10 introduced in 2015. HMRC have published updates to the Inheritance Tax Manual and guidance on gov.uk which include case study examples. In the guidance, HMRC outline a 5 step process to calculate what they call the “additional threshold”. Rather unhelpfully this is not a term used in the legislation and, to make things worse, it transpires that “additional threshold” is used to refer to two separate terms that are in the legislation “former allowance” and “lost relievable amount”. Those unlucky enough to spend too much time looking at the legislation will also find that there are 2, 3 and 4 step calculations in various sections but no distinct 5 step process. To clarify matters, I have cross-referenced the guidance to the statute in the table at the top of this article.

The 5 steps perform an interim calculation returning the “lost relievable amount” to represent the difference between the higher RNRA that would have been available on the Qualifying Former Residential Interest (QFRI, the higher value residence disposed of) and the lower (or nil) amount available on any QRI comprised in the estate. The “downsizing addition” is then calculated as the applied uplift to the RNRA used by the estate after taking into account the assets closely inherited and any tapering reduction.

The discrepancy between the guidance and the statute appears in HMRC’s step 3 which refers only to the value of the home in the estate upon death. The statute qualifies this to be only that part of the QRI that is within the chargeable transfer, VT – i.e. it excludes any part of the interest that passes to an exempt beneficiary such as the surviving spouse. The issue therefore only arises where the following apply:

- There has been a downsizing event

- There is a QRI in the estate at death

- Part or all of that QRI passes to an exempt beneficiary

The effect of this is manifested in two of HMRC’s case studies, although it takes a little reimagining as the cases themselves are too limited in scope, and the value of the assets would in practice fall within the standard nil-rate band (NRB). The two case studies appear in the guidance and IHT Manual entries under different names but are otherwise identical. The names used are Norman / Nigel / Mr N for the first case and Oliver & Karen / Mrs & Mrs Clarke / Mrs O for the second.

To illustrate the discrepancy I expanded the Oliver & Karen case study to use amounts that were sufficiently large to benefit from the RNRA, would not be subject to tapering and would show the position after both deaths. In HMRC’s example there is a downsizing in March 2016 from a house worth £300,000 (jointly owned in equal shares) to a flat (jointly owned in equal shares) worth £210,000. The study considers Karen’s death in December 2019 with her half share of the flat worth £105,000 left to Oliver plus other assets of £80,000 in her estate left to their daughter.

In my expanded version of the study I increased the value of other assets such that Karen’s half share of the property plus other assets was worth £600,000 in lifetime whilst Oliver’s assets totalled £550,000 in lifetime. I also considered the position if Oliver died in February 2020, such that the two spouses die within the same tax year. When adjusting the value of the QRI in each estate to model the various scenarios I adjusted the value of the other assets the other way to maintain the overall estate values at £600,000 and £550,000 respectively.

I calculated the aggregate tax paid across the two estates where the assets initially transferred from Karen to Oliver and alternatively as if Karen left all of her assets directly to their daughter. In all scenarios the position after second death is that all of the assets are in the hands of their daughter, and thus ultimately qualify as being “closely inherited” for the purposes of the RNRA. One would therefore anticipate that the aggregate tax charge across the two estates would be the same for all scenarios.

The tests

Let’s first consider the position that would arise if no downsizing were to have taken place. Karen’s assets would comprise a half share in the original house worth £150,000 plus other assets worth £450,000 (total £600,000) and Oliver’s would comprise his half share of the house worth £150,000 plus a further £400,000. Suppose Karen leaves everything to Oliver on her death and he leaves the combined estate to their daughter on his death. On Karen’s death there would be no IHT to pay as the transfer is fully exempt, and the NRB and RNRA would transfer in full to Oliver.

On Oliver’s death his estate would be worth £1,150,000 and his LPR would claim a double NRB of £650,000 and a double RNRA worth £300,000 in the 2019/20 tax year. The resulting IHT charge would be £80,000. It is well understood that should Karen have left everything directly to their daughter, and therefore her estate made use of her nil rate bands, the aggregate tax would be the same since the transferability acts to maintain a consistent tax treatment in such circumstances.

Limiting the downsizing benefit

Next we will look at another unequivocal situation. Here, the downsizing takes place but there is no replacement residence (no QRI upon death) and the two estates contain only general assets to the same overall values. In this case there is no discrepancy between the statute and HMRC’s interpretation since step 3 is bypassed as we have a “s8FB case”. The downsizing provisions will act to restore some of the lost RNRA but other practitioners have previously identified a planning pitfall where the resulting assets are left to the surviving spouse on first death. When the first transfer is made to the surviving spouse the assets lose their identity as a QFRI and the value of the available RNRA on second death is reduced. This issue has been raised on the Trust Discussion Forum in relation to a case where a couple have sold a house and moved into residential care.

Applying this scenario to my expanded case study, on first death the downsizing provisions restore the maximum available RNRA but its use is deferred since Karen leaves everything to Oliver. Let’s look in detail at the operation of the 5 steps upon Oliver’s death:

Step 1. Work out the additional threshold that would have been available when the former home was sold or given away or when the move happened. This figure is made up of the maximum additional threshold due at that date (or £100,000 if it was before 6 April 2017) and any transferred additional threshold available when the person dies.

The former home was sold in March 2016 so we take £100,000 as the “maximum additional threshold” and add the “transferred additional threshold” of £150,000 for which Karen’s estate qualified upon her death in December 2019. The former allowance is therefore £250,000.

Step 2. Divide the value of the former home at the date of the move or when it was sold or given away by the figure in step 1, and multiply the result by 100 to get a percentage. If the value of the former home is greater than the figure in step 1 the percentage will be limited to 100%. If the value of the home sold is less than the figure in step 1, the percentage will be between 0% and 100%.

The “value of the former home” means the QFRI comprised in Oliver’s estate which is £150,000 representing his half share. Dividing that by the former allowance of £250,000 from step 1 gives 60%.

Steps 4 and 5 have no effect as there is no QRI in Oliver’s estate (a s8FB case). The statute therefore omits these steps completely. For completeness, if we follow the steps as per the guidance, after completing step 4 we have deducted zero from the 60% in step 2.

Step 5. Multiply the additional threshold that would be available at the time the person died by the figure from step 4. This gives the amount of the lost additional threshold.

When Oliver dies the “additional threshold” available is £150,000 with respect to his estate plus 100% brought forward from Karen’s estate, thus £300,000 in total. The final step is to take 60% of that amount to give a lost relievable amount of £180,000. That same figure carries forward as the downsizing addition and ultimately the RNRA available to Oliver’s estate.

We can see that whereas it might be anticipated that the combination of downsizing provisions and transferability of the RNRA would maximise the RNRA for Oliver at £300,000 – as would be the case if no downsizing had taken place – in fact step 2 effectively cancels out the transfer of Karen’s unused RNRA since the assets representing Karen’s share of the QFRI lose their identity as such once they pass to Oliver.

When I complete the sequence of calculations the aggregate IHT charge is £116,000. Since there is no discrepancy between the statute and interpretation here we can see that this reflects a policy intent to negate the benefit of the transferability of the RNRA within the downsizing provisions where the resulting assets are not closely inherited until the second death.

The statute accidentally working as you expected it to

Now let’s consider the scenario where the issue arises, the expanded version of the Oliver & Karen case study. Here the downsizing has taken place and there is a QRI of a lower value in the estates. In this case we need to follow all 5 steps as we have a s8FA case, and we can see that the discrepancy in step 3 makes a critical difference. This time we need to look closely at the situation on first death, i.e. Karen’s.

Step 1. Work out the additional threshold that would have been available when the former home was sold or given away or when the move happened. This figure is made up of the maximum additional threshold due at that date (or £100,000 if it was before 6 April 2017) and any transferred additional threshold available when the person dies.

As before we take £100,000 as the “maximum additional threshold” available when the house was sold, but this time there is no “transferred additional threshold” as Karen is the first to die. The former allowance is therefore £100,000.

Step 2. Divide the value of the former home at the date of the move or when it was sold or given away by the figure in step 1, and multiply the result by 100 to get a percentage. If the value of the former home is greater than the figure in step 1 the percentage will be limited to 100%. If the value of the home sold is less than the figure in step 1, the percentage will be between 0% and 100%.

This time the “value of the former home” means the QFRI comprised in Karen’s estate which is again £150,000. Dividing that by the former allowance of £100,000 from step 1 gives us the maximum 100%.

Step 3. If there’s a home in the estate, divide the value of the home by the additional threshold that would be available at the date the person dies (including any transferred additional threshold). Multiply the result by 100 to get a percentage (again this percentage can’t be more than 100%). If there’s no home in the estate at the time the person dies this percentage will be 0%.

Here is where the problem arises. The “additional threshold” at the date of Karen’s death is £150,000. Whilst HMRC’s step says “divide the value of the home” which would be £105,000 representing Karen’s half share of the QRI, s8FE(9) step 2 states “Express QRI as a percentage of the person’s allowance on death, where QRI is so much of VT as is attributable to the person’s qualifying residential interest, but take that percentage to be 100% if it would otherwise be higher”. Since Karen leaves her share of the flat to Oliver it is an exempt transfer and so not comprised within VT. If we follow the statute we would take a value of zero here rather than £105,000.

- Following HMRCs method we get £105,000 / £150,000 = 70%

- Following the statute we get £0 / £150,000 = 0%

The discrepancy now carries through the rest of the calculation process.

Step 4. Deduct the percentage in step 3 from the percentage in step 2.

- Following HMRCs method we get 100% – 70% = 30%

- Following the statute we get 100% – 0% = 100%

Step 5. Multiply the additional threshold that would be available at the time the person died by the figure from step 4. This gives the amount of the lost additional threshold.

- Following HMRCs method we get £150,000 x 30% = £45,000

- Following the statute we get £150,000 x 100% = £150,000

Once we complete the calculations for Karen then Oliver’s estates using the two methods we get a total IHT charge of £98,000 from HMRC’s method and, as we would expect, £80,000 once again following the statute.

Seeing the complete picture

When I ran all of the alternative versions of my expanded scenario through my IHT calculator using both the statutory rules and HMRC’s interpretation, I returned the following aggregate IHT charges across the two deaths:

| Test Scenario | HMRC Method | Statutory Method |

| No downsizing | £80,000 | £80,000 |

| Downsizing, QRI in flat left to daughter on Karen’s death | £80,000 | £80,000 |

| Downsizing, QRI in flat left to Oliver on Karen’s death | £98,000 | £80,000 |

| Downsizing, no QRI on death | £116,000 | £116,000 |

Looking at the original Oliver & Karen scenario in isolation it might seem that HMRC’s method is incorrect as the resulting tax charge of £98,000 is out of line with our expectations that the downsizing rules combined with the provision for transferability of the RNRA would act to return the same result (£80,000) under all circumstances.

Adding in the unambiguous result where downsizing has taken place and no QRI remains allows us to see the proper context – there is a clear policy intent to restrict the benefit of transferability in downsizing cases. Some transferred RNRA will be lost with respect to the difference in value between the QFRI and QRI. If we were to repeatedly recalculate our scenarios using HMRC’s method, progressively reducing the value of the QRI from equal to the QFRI to zero we would see the aggregate tax grow from £80,000 to £116,000 as the QRI reduces to nil.

Planning notes

My discovery shows that the statute has accidentally been drafted in such a way that the result will always be £80,000 for any value of QRI that is not nil. Taxpayers are for now at an advantage unless they are unlucky enough to have downsized completely and have no QRI in the estate at death, where the policy intent is reflected in the operation of the statute.

From a tax saving point of view the planning point is clear: Where there has been a downsizing, in some circumstances (and perhaps in future all circumstances) it be necessary to pass the resulting assets to descendants at the earliest opportunity rather than via the estate of the surviving spouse. Of course, whilst tax efficient, that arrangement may not suit the needs and objectives of every testator.

For the time being the statute provides better terms on first death in the circumstances of the Oliver & Karen case. Practitioners will need to ensure that the calculations are made in line with the statute and not the (currently incorrect) HMRC guidance. I would be keen to hear of the experience of any practitioners dealing with estates that fall into such circumstances for deaths since the introduction of the RNRA on 6th April 2017.

Should the statute be amended in line with HMRC’s interpretation in due course there should be no issues on subsequent second deaths where first death occurred before any changes to the statute came into force. Of course the precise terms of any amendments will need to be reviewed to see if there are any unanticipated consequences, to ensure that the more valuable RNRA will carry forward.

What next?

As at the end of 2017, HMRC have referred the matter for ministerial review and we must wait and see if an amendment to the statute shall be made. In the meantime, they have advised me that they will be reviewing the guidance and the IHT Manual.

————-

Owner & Director

By Mark Benson TEP

Owner & Director

Capital & Professional Consulting Limited

Please contact me if you would like further details of the calculations made or would like assistance in assessing the impact on your clients.