This article is intended for professional advisers only and is not directed at private individuals.

Please use the opportunity of this Budget to sort out the IHT mess.

For the Chancellor of the Exchequer in office the relentless rise in Inheritance Tax (IHT) receipts is a helpful contribution to the Treasury’s coffers. To tax payers it is serious threat to family wealth and to one Shadow Chancellor it was a tempting vote winner. Sadly, with the votes won George Osbornes promise of a £1m Nil-Rate Band (NRB) turned into a horrendously complicated sham in the guise of the Residence Nil-Rate Amount (RNRA).

It’s time for our current Chancellor Philip Hammond to use take chance (his second) of this week’s Budget to extract us from the mess his predecessor made.

A promise, fudged

Former Chancellor George Osborne introduced the Residence Nil-Rate Amount in the second 2015 Budget as a political fudge to attempt to make good on the promise he made as Shadow Chancellor in 2007 to introduce a £1m NRB. Once Osborne became Chancellor the promise had to sit out 5 years of coalition government and ultimately give ground to the realities of post credit crunch finances and the resultant need to fill the coffers from every source possible.

The result was that the standard NRB was frozen at £325,000 from 2009 and is not currently scheduled to increase until 2021. The £1m NRB is conjured up by an additional nil-rate provision introduced from April 2017 worth £100,000 and scheduled to step up by £25,000 per year until it reaches £175,000 in 2020/21.

Whilst the RNRA “delivers” a headline £1m of nil-rated IHT transfer its introduction as an additional provision separate from the standard NRB means it significantly falls short of what was promised on the face of it. For instance:

• It applies to transfers on death only and not those made in lifetime

• To qualify a residential property interest must be “closely inherited” by descendants of the deceased thus excluding renters, siblings, friends and remoter relatives of benefitting.

• At best, it is worth £500,000 for an individual when combined with the regular NRB and only reaches that level in 2020.

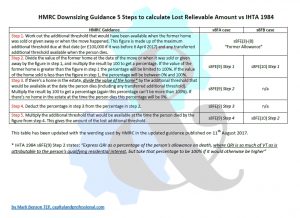

• It is so horrendously complicated with hidden planning pitfalls that currently even HMRC fail to correctly interpret it.

A quick note on the name of the provision. HMRC have an unfortunate habit of making up and using their own terms for elements of the RNRA calculation in publications and guidance. HMRC refer to the provisions as the “Residence Nil-Rate Band” or “RNRB”. However, that term is not used in the legislation, which seems to be a deliberate choice to avoid confusion between the provisions and the standard NRB. I think this is an important distinction since these provisions operate independently of the NRB – and HMRC seem to have confused themselves by making up their own terms. In this article and elsewhere I will use the correct terminology of Residence Nil-Rate Amount or RNRA.

Why we need a higher NRB

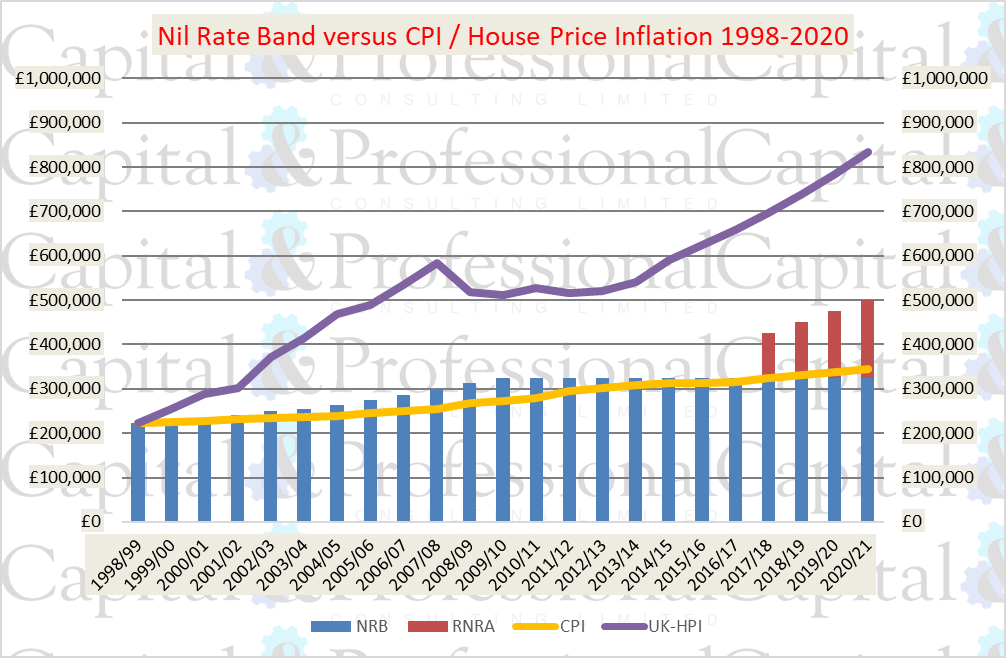

In principle tax thresholds and allowances, pension and benefit payments should index each year at the rate of inflation. In recent years the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) has been adopted in place of the Retail Prices Index (RPI) as the measure used. The key rate is the annual rate of increase in the index from September of one year to the next. The Office of National Statistics (ONS) currently publish CPI data from 1998 when the NRB for the 1998/99 tax year was £223,000. In 2017/18 the standard NRB is £325,000 representing an annual rate of indexation of 2.0% since 1998/99. The average annual rate of September CPI inflation over that period is… 2.0%.

The NRB has therefore kept up with inflation over the period, so what is the problem? The ONS’s UK House Price Index (HPI) shows an annual growth rate of 6.2% over the same period. Since value of residential property is the main driver of IHT liability for the majority of estates, this has led to a corresponding growth in IHT receipts of 5.9% p.a. over those 19 years.

Finding a level for the NRB

Whilst the RNRA is a horrible attempt to solve the problem it does provide some welcome IHT relief – an individual estate qualifying for the maximum Residential Enhancement of £175,000 in 2020/21 would save an additional £70,000 in tax versus the standard NRB alone.

A much better solution would be to find a higher level for the standard NRB that raises the amount of tax the Chancellor wants and consigns the RNRA legislation – ss8D-8M IHTA 1984 – to the dustbin where it belongs. Unfortunately, the current Chancellor Philip Hammond did not take the chance to do this in his first Budget prior to the RNRA provisions coming into force for the 2017/18 tax year. As we are now more than half way through the current tax year and the rules are being applied to actual estates, any adjustment could only really take effect from 2018/19.

Taxpayers would not want to see any reduction in the maximum possible nil-rate provision of £325,000 NRB plus £100,000 RNRA for an individual, and indeed it would be exceedingly unfair if estates in 2017/18 benefitted from a more generous level than later years. The difficulty for the Chancellor is that resetting the standard NRB to £425,000 in the current tax year would raise less tax as the qualification restrictions and taper relief would be lifted allowing more widespread application of the band.

The good news for the Chancellor is that if the standard NRB had been increased in line with UK house prices since 1998 it would be now be worth £697,000, and if we assume the same rate of growth for a further 3 years it would be on course to be £834,000 in 2020/21. So, by simply converting the scheduled RNRA into an increase to the standard NRB at the same levels the Chancellor could still preserve most of the IHT bounty, whilst freeing us all (not least HMRC) from the trauma of the RNRA.

Such a move would be a first step in delivering on the 2017 manifesto promise to simplify taxation. He could even claim he’s delivering a £1m nil rate band.

We can hope… but I’m not holding my breath. Then again as we enjoy our first pre-Christmas Budget this year perhaps my words won’t go to waste:

“Dear Santa…”

![]()

Please contact us if you would like a copy of the chart without a watermark for use in your presentations.